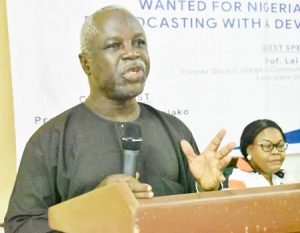

Professor Lai Oso is one of Nigeria’s most widely published communication researchers. A former Dean, School of Communication, Lagos State University, LASU, he is the national president of the Association of Communication Scholars and Professionals of Nigeria, ACSPN. In this interview, Oso speaks on some key issues on the development of journalism in Nigeria, particularly the effects of the New Media. He expresses his opinion on the raging fire of controversy over hate speech and the attempt by the government to regulate social media, among other things. Excerpts:

How would you assess the development of Journalism in Nigeria over the years, particularly in the area of its effects?

There have been changes – some quite positive, some negative. On the positive side, one would see that journalism has contributed to the widening and deepening of the democratic process in the country. So many people now have access to the media, whether traditional or the New Media. On that score, I think one can say that there has been a lot of positive things, especially when you look at accountability, with the media holding those in government accountable, trying to put some checks on the way those in government behave and how they run the policies. Critical voices are coming up through the media space. So, one can say that we have had some positive developments.

But on the other hand, there have been some drawbacks, particularly with the advent of the New Media. It is like anybody can say anything without any caution, without any sensitivity to the complexity of the Nigerian society. I’m a little bit careful using “hate speech.” It is a kind of nebulous concept that some people can easily appropriate to muzzle the freedom of the press or freedom of expression. But there are evidences that people are taking advantage of the existence of New Media and even some traditional media to propagate causes that can create problem. But I think the effect is more on the positive side than the negative side.

You talked about the advent of the New Media. Has it been given the required attention in journalism schools as to warrant a change of curriculum?

Yes, somehow. You now find out that you have courses addressing some of the concerns and challenges that are coming with the New Media in terms of how you write for the new platforms, how to manage and how to organise those new platforms. Also, attention is being given to developments in the new platforms – how to address public issues and public concerns. So, it has effect on the curriculum of communication studies.

What is your assessment of the influx of online publications as compared to the conventional ones?

I think we need to separate some of these platforms. You cannot compare Premium Times, The Cable and a few others with some online publications. Some online publications are merely online because they take advantage of new technologies. The serious ones are more or less like the traditional media in the sense that they still do gate-keeping and observe the ethics of the profession. The other ones are not bothered about all that; they are only interested in how many people visit their websites so that they can attract advertisement and so on. Those are the ones that are creating problems. But there are some that are professionally run.

Some have expressed concern over the overwhelming number of online publications. Do you share this position?

Yes, there is no doubt that people are concerned and many people are raising issues about the proliferation of online platforms. Some of them, you can’t even trace them and they can do anything and get away with it. They can open a platform today, cause havoc and move on. They have no address. It gives the people the opportunity of anonymity and all that. That is part of the problem of New Media.

But it has its positive side too. During the military era, and we have also witnessed such during this era too, where the government can move in and say “we are arresting journalists or we are closing down a media organisation.” If you do that these days, or you muzzle an editor, you are wasting your time. Even if you are the proprietor of the media organisation, you will be wasting your time because that story will have an outlet in another platform, particularly online platform.

The kind of control that those in power once wielded has reduced drastically with the arrival of some of the internet-based media outlets. When I say those in power, I mean business people, some so powerful that they can change the editorial policy of a newspaper with their advert money, or withhold certain information because they have the power of advertising. That has more or less been reduced. So, on that score, they have their uses and advantages for openness, for transparency in governance, business and things like that.

Some have complained about the infiltration of the system by some who are not journalists and carry out their work without cognizance of the ethics of the profession.

Journalism is very important but very delicate. It can be likened to dropping an egg. Once it drops, it splits and you can’t put it together. That is the danger in journalism. When you put something in the public space, it travels, it goes everywhere. Before you know it, it could ignite the crisis. That is where the issue of professionalism, ethics and social responsibility come in. If you have people who don’t have any conscious professional obligation, feel nobody can hold them responsible and they feel they are not responsible to anybody, then, you have a problem. That is where the issue of training and ethical standard come into play.

When you have so many people that don’t have these things, it is dangerous. It is like putting a gun in the hand of a child; he doesn’t know what it is; if he pulls the trigger… That’s the danger in it.

The decision of the Federal Government to regulate social media is said to be based on happenings in social media generally. I know that some time ago you said the government should rather educate the public on the use of social media instead of trying to regulate. How do you feel that the government has resolved to regulate social media despite the disapproval by individuals and organisations?

The Federal Government is acting based on fear and hysteria. We are conducting a research now on hate speech and fake news during the 2019 election. We are surprised that we don’t have so many. So, it is like there is so much noise about hate speech and fake news. One person makes a statement and everybody begins to tag on it. One is not saying there is no hate speech. There are, but they are not as big as people are making it. It is not as big to the extent that it will make us have a law that will criminalise speech and lead to death sentence. I think it is a hysterical response to a very little issue. We need to ask ourselves the question: What has brought hate speech to the front burner? It was not here some four, five or six years ago. Why is it here now? Why is there so much panic or moral preaching about it? Government has not gone into that. We need to know the source of the problem before we can think of the solution. The government is not acting as it should. All these issues about death sentence and hate speech law, I think are knee jerk reaction to something that is real but not as enormous as we are making it.

One can even conclude that the government is using the debate to divert attention from some of the crucial problems in the Nigerian society. There is a danger in that. You tend to overlook some of the critical problem and just focus on something that is ephemeral that if we do the right thing, will fade away.

The Minister of Information, Alhaji Lai Mohammed, said the regulation had nothing to do with professional journalists but those who are not guided by any rule.

It’s just the same hysterical response. I think there are enough laws to handle some of these situations. So, this kind of selective response to certain issues of the moment does not really solve any problem. Rather, they can complicate it. And it should be noted that government acquires power incrementally, particularly an authoritarian government. “Oh, we are targeting those who are not trained”, before you know it, they move on again, “We are targeting those unregistered newspapers.” Before you know it, they swoop on the established newspapers and journalists. It is an incremental thing; it doesn’t come at a go.

How best can the National Assembly be stopped from enacting the hate speech law? I’m asking this question because there are complaints in some quarters that the necessary professional organisations are not making as much noise or taking steps required to stop the move.

The Nigerian Guild of Editors has made a case against the bill. Don’t forget that the public outcry is having some impact. The man who started it all, Abudullahi, has now said, “No, we will remove the death sentence.” It is like, let opposition come from different fronts; let’s galvanise all the different groups, civil society and others for mass protest against this bill. Protest does not mean that we should carry placards. When you hear the voice of Professor Soyinka and you hear some of the governors saying we don’t want this… When all these are coming up, they will have a rethink. People in the National Assembly are also human beings. I heard some people in the House of Representatives saying that the bill would not pass through in the House of Representatives. That means that the outcry from civil society organisations is having some effects.

The coming of the online platforms has put most of the conventional newspapers on their toes as stories are rendered stale before they can publish them the next day. How best can they solve a problem as this?

What will sell the conventional newspapers today is not just breaking news because they can’t compete with the online platforms. Where they can have an advantage is where they put the issue in proper context. So, it is not just the question of informing, they should be more interested in educating the public like doing analyses, providing background information, doing well researched feature articles and carrying out investigative journalism and so on. These are the areas the conventional newspapers can focus on.

You would realise that most of them now have online versions, but they must go back and put things in perspective for the next day. That is how they can still have an advantage.

With recent developments, what would you say is the future of the conventional newspapers?

There is a future. There are people who would, like I said, still want to read the news behind the news. What is the context? What does it mean? The conventional newspapers must continue to provide meanings to events – the context, the background. Online platforms cannot do such creditably except they want to wait till the next day. Immediately the news break, they report. But people would want to know what it means. That is the future of the newspapers. And of course, they must have online versions where they can also break the news and the following day, they put them in perspectives.

Apart from the challenges posed by the online platforms, the conventional newspapers are facing other problems which have made it impossible to pay salaries, take care of certain basic needs to keep the organisations running. What are the problems, really?

The problems are many. A major one has to do with advertisement. Advertisers are moving to online platforms; the young people are also moving online. You would find out that the advertisement rates online are a little bit lower than what you get in the conventional media. Why would you go to the conventional newspapers if you can reach your target audience – these upward mobile young men who are checking their phones even in the bus and okada. If your advertisements are able to read them, then you would not want to go to the newspapers. That is one problem.

Two: The economic situation is affecting them. Time was when people would buy three, four newspapers in a day. Hardly can people buy one now because of the economy. The disposable income available has gone down considerably. That has affected circulation. That has affected adverts. These are some of the challenges that they face. That is why some are saying that there should be a new business modem. Like what is happening now in Guardian in London. They are now asking people to support them, and they are getting a lot of support with people donating. Some other newspapers are going into some other businesses where they can still make money and support the publication of the newspaper. They need to think outside the box. They cannot rely on the old modem and survive; they need to re-engineer their thinking and get into new business activities to support the newspapers especially if they want independent newspapers.

There are numerous awards coming up these days. Would you say they are actually contributing to the growth of journalism?

Yes, if they are genuine awards and by genuine organisations. I know of three awards for journalism in this country that are quite credible –Wole Soyinka Award for Investigative Journalism, DAME, and the Nigerian Media Merit Award. Those three are credible. Those who are behind them are also credible. But, there could be others that I don’t really know about. My only fear is about journalists giving awards to those they should report. You find beat associations coming together to give award to people like the “Best Governor of the Year,” the “Best Minister of the Year” and so on. That is where the danger is. It is not their business to be celebrating those they should be reporting. Let those who read their reports celebrate them. I’m also not too keen in journalists taking awards from government. If the award is organised by government, I think one should be careful about it.

Why is that so?

I read a book about investigative journalism. The author said when the dog that is supposed to be watching somebody begins to eat with those that it is watching, then there is a problem; the bite is gone. That is where my fear is.

What is your opinion about the awards judged through voting on the internet without necessarily reading the works of those contesting?

I don’t support that. You find out that those nominated begin to campaign, sending text to you saying, “vote for me, vote for me.” Those who are voting don’t even know them. They’ve never read them. That is the kind of thing they do in Big Brother. It shouldn’t go into a professional award. You don’t hear Nobel Award saying the global community should vote for those to be awarded. Those are cheap awards that are tagged to entertainment and celebrities. It shouldn’t be for credible professionals.

Based on your position about the kind of relationship that should exist between a journalist and those in government, to what extent should a journalist be close to those in government.

It is a very dangerous thing. It is a very slippery ground. Once you get too close, you get compromised; you become embedded and you begin to see things from the perspectives of those you are reporting. Then you lose your autonomy, you lose your integrity, and the freedom of the press becomes a casualty. So, journalists must be careful in their relationship with those in power.

ALSO READ: 13 journalists, others honoured at Wole Soyinka Awards

But it is obvious that some journalists get close to those in government because their employers don’t do what they should in terms of remuneration and general welfare.

You are right. It is a very complex issue. Once you employ people and you outsource the welfare of your reporters to sources, you have lost your autonomy. I think that is not the traditional liberal perspective of journalism. So, we need to do something in that area. If you want a free press, there must be a way of insulating journalists from the powers that be.

What tips would you, as a teacher, give to strengthen journalism practice in the country?

We should strengthen the issue of ethics.

How should we do that?

I think the professional bodies should look at a way that if a journalist offends, he should be made to pay for it. In the present situation, except the National Broadcasting Commission which is saying that if you don’t do your work the way it should be done, you shall be sanctioned according to the law… And that only happens during the election period. They sanction the organisations. What of individual journalists? You get something published which you know is false, or you are caught taking bribe and the organisation closes its eyes as if nothing happens. The Nigerian Press Council cannot do anything. I think we need to strengthen that area. We need to increase the level of adherence to ethical standards.

Then of course, training. You find out that some media organisations have not trained their reporters in the last ten years. These are people that are doing the work for you. You cannot even organise in-house training for one day to improve their capacity. We need to do a lot in the area of capacity building in journalism.

We have some organisations that have been helping out in that area, but some of them are dismissed as feasting on the money they collect from donor agencies.

Why would anyone complain? As far as the money they get is being spent well, people are benefitting, I’m all for it. Somebody must pay for the work they do. If Nigerians are not ready to pay, somebody must pay. There is something we call the third sector. That is where you have the philanthropists or foundations that are ready to put in money. You don’t have many in Nigeria, and the ones that are here want to put money where they will get publicity and all that. We have the IPC (International Press Centre) by Lanre Arogundade, Wole Soyinka Centre, Lanre Idowu and others. If they get money and spend it well in improving journalism, I don’t have any problem with that. Somebody must pay for it if Nigerians are not ready to do that.

Look at the immunisation being carried out all over the place. Who is paying? They are international organisations. The Nigerian government is not doing much. We get much of the HIV drugs from outside. Bill Gates and the rest of them pay the bills. So, why would anyone complain?

You started as a reporter in a radio station, then News Agency of Nigeria. What informed your crossing from the newsroom to the classroom?

The person that has influenced me most in my career has been the late Professor Femi Sonaike. He was a reporter before he went into academic. I think that influenced me.

How did you meet him?

He was my lecturer at the University of Lagos; he supervised my BSc project and he was monitoring me after graduation. So, when I was doing Masters, it was that time they started Moshood Abiola Polytechnic’s Mass Communication programme. He crossed from UNILAG to start the programme. So, he more or less brought me into academic, and I’ve since been there. And I met some people in academic who had been professionals, like Professor Idowu Sobowale who had had a lot of influence on me; and Professor Olatunji Dare. These are people who are professionals, who are also in academic.

Having been part of the two worlds, is there a relationship between the newsroom and the classroom in journalism?

Yes. Well, your experience in the newsroom tends to, in a way, influence your academic work in terms of research. You already have some professional practical experience. By the time you put that into the theory, you see where there are some differences, where there are some similarities and that could influence the way you do things.

ALSO READ: Community media key to national development ― OGTV GM

Would you say the schools have been able to bridge the gap between the theories taught in the classroom and the practical aspects experienced on the field in journalism?

The schools of journalism have not been able to do that. The department of Mass Communication still needs to do a lot in coming to terms with the development we have seen in the communication arena in terms of technology in particular. How do we get our students to get a good handling of these technologies? We have a good number of students who are now into digital photography, who are now into multi-media. We can still do more if we have access to fund. We would like to bridge the gap between town and gown. I would like to see a situation where some of our colleagues who are in the industry, who are professionals, can be allowed to come as lecturers to teach. It should be a structured process and not just bringing them in to give lecture or talks. It should be a structured process so that we can benefit from what they are doing.

What’s your philosophy of life?

Simplicity. I take things easy and stay humble?

How has that philosophy helped you?

It has helped me a lot. I feel relaxed in any group – with my students and with people generally. I can relate with them well and they can relate with me. There is no social barrier. I don’t encourage social barrier. I relate with any human being as one created by God with some unique perspectives, unique attributes. I tend to relate with those unique attributes of the individuals. People have their strength, so I try to relate myself to the strength of the people I interact with. I don’t really look at your weaknesses. We all have our weaknesses and strength. If you relate to people’s strength, and you help them to develop those strength, people will benefit.

How best can the university system be improved?

We have a lot of areas and one of them is funding. Another is improving our students. You have a good number of our students and it is like they are being forced to be there. Even when they get the admission, their heart and soul are not in the system. We have many of them. That discourages you as a lecturer. That was not the same thing that happened in the past. The kind of books we read as 100 level students they can’t read them now. They don’t have the kind of exposure we had. 400 level students are afraid to read some of the books and the articles you like them to read. They don’t bother. Some of them are in schools because of funding. The universities want them because they pay school fees. You find them in all higher institutions. Students population has grown so high that you can’t even cope. In a journalism class where you have about 300 students, how do you give them reporting assignments? In our days at the University of Lagos, each of us would write at least two stories in a week and it would be graded. You can’t do that now. So, it is affecting the system. You find those that are very good, but it is like you put rotten apples with good apples, the rotten ones will affect the good ones. And where the rotten ones are so many, it is a problem.

What advice would you like to give to those who would like to practise journalism and those who would want to teach?

There is one statement which we were taught as undergraduates: Journalism involves knowing something about everything and everything about something. Yes, you are a lecturer, you teach journalism, you teach broadcasting, you teach film; you are an expert in the field, but you must know something about other areas. Communication is everything about us. It is all over us. So, you must have a very good grip of the totality of communication.

What advice would you also like to give in general?

Government and civil society groups have to do something about public knowledge and public understanding of issues. We are not doing that. For instance, people don’t know enough about Nigeria. It is a pity. You find young people born in Ojo local government area of Lagos State, where we have Lagos State University; they had a primary school in Ojo local government; secondary school in Ojo local government, LASU or at best they go to UNILAG for their university education; all still in Lagos. When it comes to the issue of NYSC, their parents are working to ensure that if at all they are going to go out, it is not beyond Oyo State. And these are people who will become Editors, who will write about Nigeria. Many of our young people don’t know this country. That is why it is easy for politicians to play on ethnic and religious fears. “Oh, the Yoruba are like this,” and because you never interacted with them you accept. “The Ibo are like this.” Except you are born in some parts of Lagos where you have seen some Ibo, you would not know what they are. And, if you go to the East, you will realise that the Ibo of Lagos are not the Ibo of the East. “The Hausa are like this,” “the Fulani are like this.” We don’t know ourselves. We need to find out how to deepen the inter-ethnic virtue and knowledge. How do we know about the complexities of Nigeria that we can have a good understanding and appreciate what Nigeria is? I think that is very important. The government owes that responsibility. We need to go back to the teaching of Civic, History from primary school to secondary school and up to the university. That means that the government must be ready to teach us with the publication of books that will reflect the diversity and the complexity of Nigeria. How do we use television? How do we use the Nollywood to preach national unity from a very comprehensive perspective, showing the diversity of this country that we can appreciate? We have the instrument – what people call soft power. We have television, Nollywood, our books, plays, novels. How can we use them? It is a duty that the government owes us.

- This interview first appeared on FRONTPAGE